สุราโบราณของญี่ปุ่นที่ชื่อ “โดบุโรกุ” ซึ่งครั้งหนึ่งเคยเป็นของต้องห้ามเนื่องจากการควบคุมของรัฐบาล กำลังกลับมาเป็นที่รู้จักอีกครั้ง โดย Heiwa Doburoku Kabutocho Brewery ได้เปิดบาร์เฉพาะทางแห่งหนึ่งในย่านนิฮงบาชิ โตเกียว เพื่อให้ชาวเมืองและนักท่องเที่ยวได้สัมผัสรสชาติของเครื่องดื่มพื้นบ้านชนิดนี้ โดบุโรกุเป็นเครื่องดื่มแอลกอฮอล์ขุ่นที่มีรสชาติแตกต่างจากสาเกทั่วไป มีกลิ่นและรสชาติที่เข้มข้นกว่าสาเก ด้วยกระบวนการผลิตที่ใช้ข้าวและเชื้อหมักรวมกันในขั้นตอนเดียว ส่งผลให้ได้รสชาติหวานอ่อนและมีแอลกอฮอล์ต่ำกว่า

โดบุโรกุคืออะไร

โดบุโรกุเป็นสุราที่มีประวัติซับซ้อนไม่ต่างจากลักษณะของมันเอง ซึ่งเป็นสุราขุ่นที่แตกต่างจากสาเกทั่วไป คำว่า “โดบุโรกุ” (濁酒) หมายถึง “สุราขุ่น” หรือน้ำหมักที่ยังไม่ผ่านการกรอง ในญี่ปุ่นจะมีสุรา 2 ประเภทหลักที่แตกต่างกัน คือ “เซชู” (清酒) หรือสาเกที่ผ่านการกรองให้ใส และ “โดบุโรกุ” ที่ยังคงขุ่นโดยธรรมชาติ

กระบวนการผลิตของสาเกทั่วไปและโดบุโรกุมีความแตกต่างที่สำคัญ สาเกใช้ยีสต์เป็นตัวตั้งต้น และมีการใส่ข้าวนึ่ง โคจิ (เชื้อราข้าว) และน้ำเพิ่มลงไปในหลายวัน แต่การผลิตโดบุโรกุจะใส่ทุกอย่างรวมกันตั้งแต่แรก ซึ่งทำให้เกิดการหมักที่มีปริมาณน้ำตาลมาก จึงทำให้ยีสต์เริ่มย่อยสลายเร็วขึ้นและหยุดการหมักได้เร็วกว่า ซึ่งส่งผลให้โดบุโรกุมีรสหวานกว่าและมีแอลกอฮอล์ต่ำกว่า

ทำไมโดบุโรกุถึงกลายเป็นสุราต้องห้าม

โดบุโรกุเป็นสุราที่ชาวไร่และนักบวชชินโตนิยมดื่มในญี่ปุ่นมาเนิ่นนาน เนื่องจากมีวิธีทำที่เรียบง่าย ชาวบ้านจึงทำสุรานี้กันได้เองทั่วไปในชนบท มีรายงานว่าในปี 1855 มีผู้ผลิตโดบุโรกุกว่า 459 แห่งในเอโดะ (โตเกียวในปัจจุบัน) แต่เมื่อสิ้นสุดยุคเอโดะ ระบบการปกครองถูกเปลี่ยนเป็นรัฐบาลเมจิที่เน้นการรวมศูนย์อำนาจและการเก็บภาษี จึงได้เริ่มจำกัดการผลิตสุราภายในบ้าน

ตั้งแต่ปี 1880 รัฐบาลเริ่มจำกัดปริมาณสุราที่ผลิตเองได้ และในปี 1882 ได้แนะนำระบบใบอนุญาตผลิตสุรา จนในปี 1899 มีการออกกฎหมายห้ามการหมักสุราในบ้านอย่างเป็นทางการ ทำให้โดบุโรกุกลายเป็นสุราผิดกฎหมายที่เรียกว่า “มิตซึโซชู” หรือสุราที่ผลิตลับ ๆ

แม้จะมีกฎหมายห้าม แต่โดบุโรกุก็ยังถูกใช้ในพิธีกรรมของศาลเจ้าชินโต หลังสงครามโลกครั้งที่ 2 ชาวญี่ปุ่นใช้เครื่องดื่มจากเกาหลีที่เรียกว่า “มากกอลลี” ซึ่งเป็นเครื่องดื่มที่คล้ายโดบุโรกุแทนในช่วงที่ขาดแคลนสาเก ในปี 2003 รัฐบาลญี่ปุ่นได้อนุญาตให้บาร์และร้านอาหารในบางพื้นที่ที่ต้องการฟื้นฟูเศรษฐกิจผลิตและจำหน่ายโดบุโรกุได้อย่างถูกต้อง และ ณ ปี 2021 มีสถานที่ที่ได้รับอนุญาตกว่า 193 แห่งทั่วประเทศ

สถานะของโดบุโรกุในปัจจุบัน

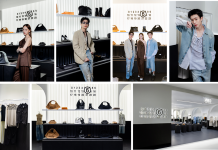

บาร์ Sake Hotaru ในโตเกียวเป็นแห่งแรกที่สามารถขายโดบุโรกุได้อย่างถูกกฎหมายตั้งแต่ปี 2015 จากนั้นบาร์อื่นๆ ก็เริ่มเปิดให้บริการ โดยในเดือนมิถุนายนปี 2022 Heiwa Doburoku Kabutocho Brewery ก็ได้เปิดบาร์ในย่านนิฮงบาชิ ซึ่งดึงดูดลูกค้าชาวต่างชาติเป็นจำนวนมาก โนริมาสะ ยามาโมโตะ ประธาน Heiwa Shuzou กล่าวว่า ลูกค้าชอบถามเกี่ยวกับความแตกต่างระหว่างสาเกกับโดบุโรกุ กระบวนการผลิต และเวลาที่ใช้ในการหมัก

นอกจากโดบุโรกุแล้ว บาร์ยังให้บริการสาเกและเบียร์ที่ทางโรงกลั่นผลิตเอง โดยบาร์นี้จะไม่รับเงินสด และลูกค้าจะได้ลิ้มรสโดบุโรกุที่มีรสชาติเข้มข้น มีรสเปรี้ยวคล้ายกับชีสเชดดาร์และผลโนนิที่มีรสชาติเป็นเอกลักษณ์

สำหรับผู้ที่อยู่ต่างประเทศและสนใจลิ้มลองสุราโบราณนี้ Kato Sake Works ใน Brooklyn สหรัฐอเมริกา ก็มีบริการโดบุโรกุเช่นกัน แม้ผู้บริโภคในต่างประเทศยังไม่คุ้นเคยกับเครื่องดื่มชนิดนี้มากนัก แต่ Kato ตั้งเป้าว่าจะช่วยขยายการรับรู้ถึงโดบุโรกุผ่านการนำเสนอให้กับผู้ที่สนใจ

Once illegal, this Japanese alcohol is making a comeback

Japanese-produced whisky, nihonshu (sake), and beer are popular around the world.

But one bar in Tokyo has been trying to reintroduce to locals and visitors alike a taste of doburoku, one of the oldest and most controversial drinks in Japanese history.

Heiwa Doburoku Kabutocho Brewery is in the Nihombashi neighborhood in eastern Tokyo. During the Edo period (1603 – 1868), this area flourished with activity due to boats carrying shipments of sake.

With that in mind, Heiwa Shuzou (Brewery), which since 1928 had been producing sake in Wakayama prefecture, chose to open this rare doburoku specialty bar in one of the city’s upscale neighborhoods.

Before venturing into the bar to try a glass, here’s what to know about this historic, controversial tipple.

What exactly is doburoku?

The history of doburoku is as murky as the drink itself.

Often considered to be the ancestor of today’s sake; it is no coincidence that the characters comprising the word, 濁酒, signify “cloudy,” or unrefined, liquor. To distinguish this type of turbid Japanese alcohol from that of the ubiquitous and transparent sake, there are two distinct if slightly misleading categories: seishu (清酒), or clear sake, and doburoku (濁酒).

Consequently, sake and doburoku have one key difference in their respective productions.

Typical sake calls for a yeast starter, called shubo, and adding three main ingredients –steamed rice, kouji (moldy rice fungus) and water – over a period of days.

However, when making doburoku, they are all simultaneously placed in with the yeast starter, causing the resulting mixture to be comparatively overflowing with sugars. The sugars then start to break down the yeast, which halts fermentation much earlier on. Ultimately, what remains is a sweeter liquid with a much lower alcohol content, formally known as doburoku.

Why has doburoku been considered controversial?

For nearly as long as rice has been cultivated in Japan, doburoku has existed. It was the brew of choice for farmers and Shinto priests alike. With a relatively simple recipe – i.e. throwing everything into the proverbial crucible at once – doburoku was a common sight throughout the countryside.

The open practice of homebrewing continued unabated for centuries.

According to Utsunomiya Hitoshi, director of the Japan Sake and Shochu Makers Association (JSS), in 1855 there were 459 doburoku producers in Edo (present-day Tokyo) alone.

Yet, as a result of the end of the Edo period (1603 CE – 1868 CE), all feudal lords were forced to abandon their regional domains in the name of the centralized Meiji government, based out of the new capital Tokyo. Borne out of the 180-degree shift in governance came highly structured institutions, including an empowered and regimented tax collecting body.

Realizing that licensed breweries and distilleries were a vital source of income for the new government, measures to limit homebrewing began to take effect.

Utsunomiya says that 1880 is when the quantity of homebrewed liquor started to be restricted, while in 1882 a licensing system was introduced. Then, in 1896, a liquor tax was imposed on all homebrewing, culminating in the complete prohibition of homebrewed liquors in 1899.

In essence, all doburoku made from then on came to be called mitsuzoushu (密造酒), “secretly produced alcohol,” or moonshine.

However, even during that prohibition, doburoku could still be found in Japan. Tellingly, Shinto shrines were able to carry on using the beverage for rituals. After World War II, due to a shortage of sake, the Korean beverage makgeolli, an unfiltered cousin of doburoku made of rice, wheat, malt and water, was a popular alternative.

In spite of the fact that homebrewing is still illegal, the Japanese government allowed for inns and restaurants in special deregulation zones, primarily in regions where economic growth had stagnated, to commercially sell doburoku in 2003.

As of 2021, there are 193 establishments around the country authorized to sell doburoku.

The state of doburoku today

Opened in 2015, Tokyo’s Sake Hotaru was the first legal spot to offer doburoku in Japan’s capital. But bar owners only started selling it to the public in late 2016.

Since then, more options have appeared. Most prominently, in June 2022, the previously mentioned Heiwa Doburoku Kabutocho Brewery opened a bar near Nihombashi.

Norimasa Yamamoto, President of Heiwa Shuzo, estimates that half the bar’s visitors are from overseas.

“We often receive questions about the difference between sake and doburoku, how many days it takes to make it, and how it’s produced,” he says of the bar patrons.

In addition to doburoku, the brewery’s own sake and beer labels are available. However, keep in mind that if you want to order anything, the brewery does not accept cash.

The flavor is intense, with samplers comparing it to both cheddar cheese and noni, a unique-tasting Polynesian fruit.

And travelers unable to make it to Japan can sample doboruku closer to home. In Brooklyn, Kato Sake Works sells small amounts of the drink.

However, owner Shinobu Kato says “the context doesn’t exist here,” as Americans are less likely to have heard of doboruku.

“Apart from a few sake shops that are very familiar with and interested in our doburoku,” Kato says, “most of the sales are at the taproom for both bottle to go and drink by the glass.”

By Jonathan DeLise, CNN